This is a summary of my presentation in my first Rinko at the University of Tokyo. Rinko (輪講) is a course for each graduate student to join mandatorily until their graduation in the EEIS Department. In this course, students need to prepare a presentation each semester to show their survey of research topics, research progress, and results. In my first Rinko, I chose the topic of learning-based quadruped robot visual locomotion.

Abstract

Locomotion presents a fundamental and ubiquitous challenge in the field of quadruped robot research. Recent advancements in robot hardware and reinforcement learning technologies have enabled these robots to exhibit agile locomotion within complex environments compared with traditional optimal control-based methods. This integration is achieved through sophisticated sim-to-real methods such as hierarchical formulation or distillation techniques. This survey aims to introduce the fundamental two-stage training framework for quadruped robot locomotion control via reinforcement learning, along with several notable achievements derived from this approach. Additionally, it will evaluate recent progress in this area and explore potential directions for future research.

Introduction

Legged robots show great potential to navigate in complex and challenging environments. Compared with wheeled robots, legged robots have the ability to traverse complex terrain, such as stairs, slopes, and uneven ground. With a sufficiently diminutive size and also a considerable stature that enables the quadruped robot to carry the requisite payload, three prominent and highly recognized robots, Spot, Unitree series, and Anymal, show great success in numerous applications.

The empirical demonstration of quadruped robots’ maneuverability across diverse terrains establishes their commendable performance. Various methodologies are utilized to enable quadruped robots to navigate diverse terrains, with a notable focus in recent years being on learning-based approaches [1][2][3][4][5][6]. The following figure exemplifies the captured action sequences using a single neural network operating directly on depth from a single, front-facing camera for governing locomotion in a quadruped robot [6]. With such methods, these robots are capable of performing walking, trotting, climbing, and jumping in various indoor and outdoor environments.

To enable quadruped robots to perform agile maneuvers akin to their biological counterparts, like dogs or cats, it’s crucial to explore and understand the robot’s action space thoroughly. Inspired by curriculum learning, an incremental hardness training strategy is used to adapt the difficulty level for each terrain type individually [7][8]. Beyond merely enabling robots to walk or move on uneven terrain, some researchers are transforming quadruped robots into mobile platforms by attaching robotic arms, thus enabling them to perform various mobile manipulation tasks [9]. Furthermore, the robot itself can also function as a manipulator, interacting with objects in various ways, such as pressing buttons, opening doors [10], or manipulating large objects [11].

Based on the above description, the robot can execute multiple action sequences with visual image inputs. Therefore, it is natural to consider linking these capabilities together to achieve fully agile navigation. Recently, some researchers decomposed the quadruped robot navigation problem into three parts and solved the navigation problem using a hierarchical network [12]. Others distillate the specialist skills to train a transformer-based generalist locomotion policy to finish a self-designed obstacle course benchmark [13].

In this survey, we would like to introduce and discuss the following topics:

- Some necessary background of reinforcement learning (RL) and imitation learning (IL) algorithms.

- Basic two-stage training framework of quadruped robot locomotion control using reinforcement learning and some variations and their comparison between visual input network structures.

- More motions beyond just walking: after improving training environment configurations, we can let the robot perform more naturalistic and dexterous actions.

- The utilization of existing locomotion techniques to achieve agile navigation.

The subsequent four chapters will detail these topics, each addressing a specific aspect. The final chapter will present the conclusion and outline avenues for future research.

Background

Reinforcement learning

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a domain of machine learning where an agent learns to make decisions by interacting with an environment. Deep Learning (DL), on the other hand, has shown remarkable success in handling high-dimensional data, like images and natural language. It leverages neural networks with multiple layers to extract features and learn representations from large amounts of data. The integration of RL with DL, known as Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), combines the decision-making prowess of RL with the perception abilities of DL, allowing agents to learn from raw, high-dimensional data and make complex decisions.

Reinforcement learning always models the interaction of the robots and the world as a Partially Observed Markov Decision Process (POMDP). The POMDP is defined as a tuple $(\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{O}, T, P, r, \gamma, \rho_0)$, where $\mathcal{S}$ is the state space, $\mathcal{A}$ is the action space, and $\mathcal{O}$ is the observation space. $T$ denotes the transition probability distribution which describes the model of the environment as $T(\textbf{s}_{t+1}|\textbf{s}_t, \textbf{a}_t)$. $P$ is the observation probability of the form $P(\textbf{o}_t|\textbf{s}_t)$ denotes the sensor model. $r: \mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{A} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ denotes the reward function, $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is a discount factor and $\rho_0$ is the initial state distribution.

The agent interacts with the environment by taking actions $\textbf a_t\in \mathcal{A}$ at time step $t$, and receiving rewards and observations $(\textbf r_{t}, \textbf o_{t+1})$. This may repeat for several steps, and the agent will receive a trajectory: $\tau = {(\textbf o_t, \textbf a_t, \textbf r_t, \textbf s_{t+1})|t=1,2…n }$, where $T$ is the time horizon. Then the agents update their policy $\pi_\theta$ using the trajectories. The goal of reinforcement learning is to learn a distribution over actions conditions on observations $\textbf o_t$ or observation histories $\textbf o_{t:t-h}$ with the form $\pi_{\theta}(\textbf a_t|\textbf o_{t:t-h})$, which maximize the sum of the discounted rewards, which is formulated by:

\[\pi_{\theta}(\tau) = p_{\theta}(\textbf{s}_1, \textbf{a}_1, ..., \textbf{s}_n, \textbf{a}_n) = p(\textbf{s}_1) \prod_{t=1}^n \pi_{\theta}(\textbf{a}_t|\textbf{o}_{t:t-h}) T(\textbf{s}_{t+1}|\textbf{s}_t, \textbf{a}_t)\] \[\theta^* = \arg\max_\theta \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim p_{\theta}(\tau)} \left[ \sum_{t=1}^n \gamma^t r(\textbf{s}_t, \textbf{a}_t) \right]\]Here $\theta$ is the parameter of the policy $\pi_{\theta}(\textbf a_{t}|\textbf{o}_{t:t-h})$. In deep reinforcement learning, the policy is usually parameterized by a neural network.

Imitation learning

Imitation learning, also known as behavioral cloning, is used to train a policy to imitate an expert’s behavior, which may originally come from the automated driving area [14]. Given a dataset with observations and demonstrations, the policy is trained to minimize the difference between the output of the policy and the demonstration to imitate the expert.

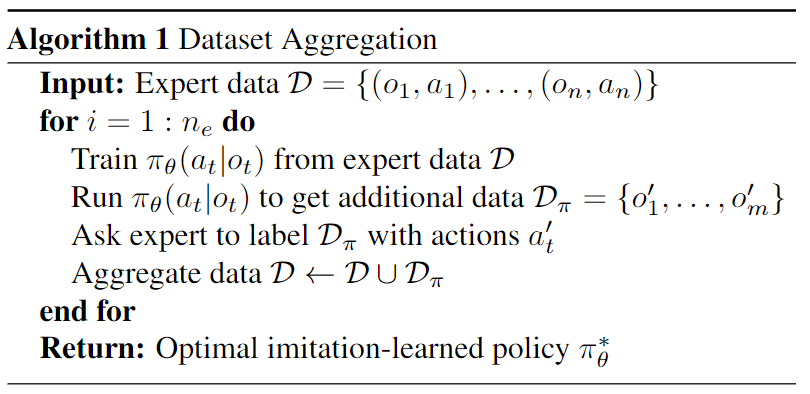

However, one of the problems is that the policy may drift away from the expert’s behavior due to the compounding error. For example, the agent may make a small mistake and be in a slightly different state from what it has trained before, thus diverging from the learned trajectory. To solve this problem, researchers propose a method called Dataset Aggregation (DAgger) [15]. In DAgger, the policy is trained on the dataset collected by the previous policy, which can be treated as a form of iterative imitation learning.

Two-stage training framework

In order to accelerate the training process, most researchers in the field of quadruped robot locomotion control use a two-stage training framework [1][16][2][3][17][6][18] instead of training the visual policy end-to-end. Another choice is asymmetric actor-critic methods [19][20]. However, we are not going to cover this algorithm in this survey.

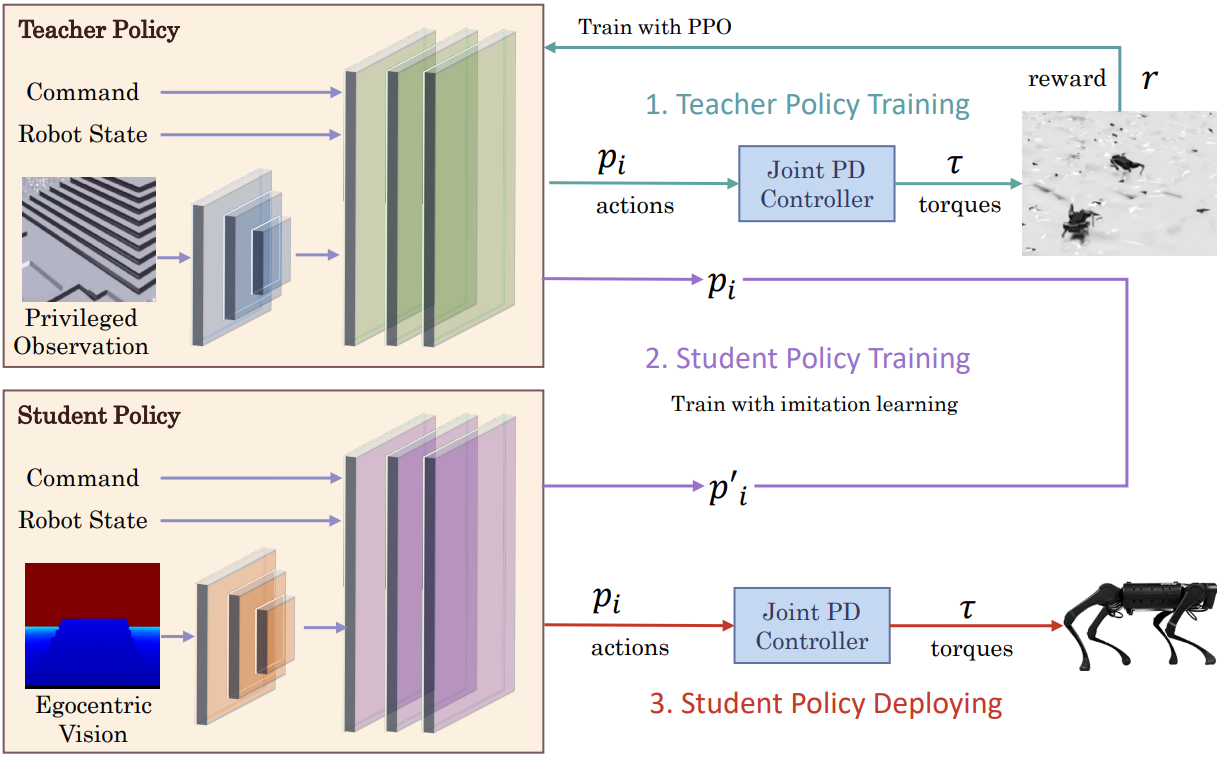

In the two-stage framework, the elevation-map-based policy is trained first, named oracle policy; then, it is distilled to visual policy using only visual inputs, named student policy. The following figure shows the two-stage training framework. The actions from the policy specify target positions for proportional-derivative (PD) controllers positioned at each of the robot’s joints, which in turn produce control forces that drive the robot’s motion.

Train the oracle policy

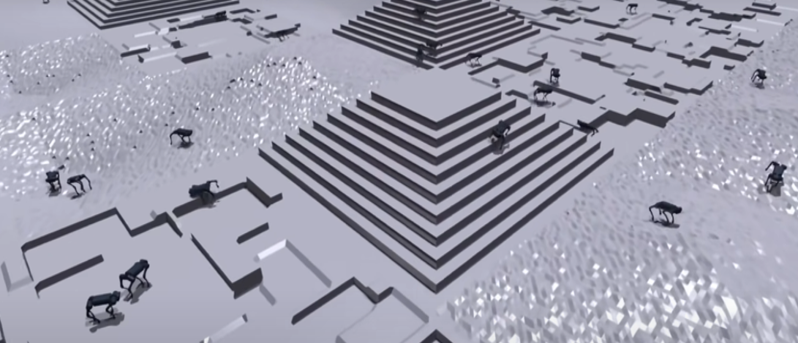

The oracle policy is trained in simulation using proprioceptive measurements of the robot and the elevation map as the input. The elevation map is a 2D grid that is usually generated by the height map of the terrain and the robot’s position. A training environment built in isaac-sim is demonstrated in this picture.

With proprioceptive information (in another word, robot state), a random input command $\textbf{v}^{cmd}= [v_x, v_y, \omega_z]$, and privileged information (usually elevation maps or scan dots) as observation $\hat{\textbf{O}}_t$, an oracle policy network module $\hat{\pi}$ is trained to output desired joint angles $\hat{\textbf{P}}_t$ for 12 motors. This process can be treated as an ordinary reinforcement learning problem and using some classical algorithms such as the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm [21] to maximize the final return.

The reward function is usually defined by several parts to let the robot follow the command while avoiding falling down and colliding with obstacles. Although the reward function in one step $\sum_i R_i$ may slightly vary in different papers, the following parts are usually included:

- Command tracking: $R_{c} = abs(\textbf v^{cmd} - \textbf v)$ where $\textbf v$ is the robot’s velocity provided by the simulator.

- Energy penalty: $R_{e} = -abs(\mathbf \tau)$ where $\tau$ are the torques applied to each motor. This part is aimed to encourage the robot to use as little torque as possible.

- Natural reward: This reward $R_n$ lets the robot learn to walk naturally to have a more visually appealing behavior. In [7], the researchers set this reward as the difference between the current joint position and the initializing joint position of the robot. Furthermore, in [17], they use a learned task-agnostic style reward, which specifies low-level details of the behaviors that the character should adopt when performing the task and is modeled with a learned discriminator proposed in [22].

The final accumulated discounted return function is defined as follows:

\[R = \mathbb{I}_{Coll}(\sum_{t=0}^{T-1}\gamma^t(\sum_i R_i))\]Here, $\mathbb{I}_{Coll}$ represents the collision flag, indicating whether there is a collision between the robot body and the terrain or obstacles. When a collision occurs, the episode terminates, and the reward is set to a scalar value less than zero.

One thing that needs to be pointed out is that by using massive parallelism on a single GPU, we can train the oracle policy with thousands of simulated robots in parallel [7]. In this research, they use an automated curriculum of task difficulty to learn complex locomotion policies. By assigning a terrain type and a level that represents the difficulty of that terrain, the robot will start on more difficult terrains once it has mastered the easier ones. After training the Unitree robot in around 20 minutes using an automated curriculum of task difficulty by a single RTX 3090, the robot is able to walk on uneven terrain, stairs, and slopes.

Distillate to visual input

Unlike privileged information in the simulator, such as height maps of robot surroundings, the visual inputs of the robot in the real environment are usually some egocentric visual input depth images or lidar signals. Therefore, we need to distillate the oracle policy into a visual policy using only visual inputs, which can be treated as an imitation learning problem.

For the student policy $\pi$, the input observations $\textbf{O}_t$ still include a random command and proprioceptive measurements of the robot, and its output $\textbf P_t=\pi(\textbf O_t)$ has the same format as oracle policy. However, the robot only has access to visual inputs instead of an elevation map, which is the same as the real-world scenario.

With designed visual input network, the student policy is usually trained to imitate the oracle policy using Dataset Aggregation (DAgger) algorithm [15] to solve the drifting problem during imitation [6][2][1][3][8]. The loss function is mainly defined to minimize the difference between the output of student policy and oracle policy:

\[\mathcal{L}_{BC} = \mathbb{E}_{\textbf{O}_t, \hat{\textbf{O}}_t, a_t\sim \pi} [D(\hat{\pi}(\hat{\textbf{O}}_t), \pi({\textbf{O}}_t))]\], where $D$ is the divergence function to measure the difference between two outputs.

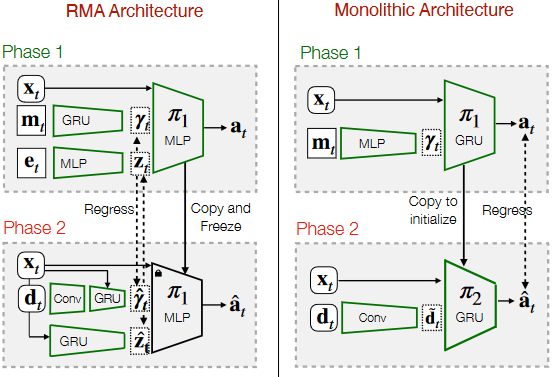

3D representation for visual input

Most naive visual input networks are based on CNN and gate recurrent units (GRU). In RMA architecture [2], during student policy training, they directly copy and freeze the MLP decoder part of the oracle policy and perform regression between latent vectors calculated by privileged information and visual inputs. On the other hand, in monolithic architecture [3], they use a CNN to extract features from visual inputs and concatenate them with the robot state, then use a GRU to encode the features and do regression on final target actions. These two architectures are compared in the following figure.

Due to partial observability, the robot relies on past knowledge to infer the current, and it is hard for it to distillate the oracle policy completely. Therefore, researchers follow the paradigm in computer vision [23] to propose a geometric memory architecture named neural volumetric memory (NVM) [17] to help the robot infer the terrain beneath it.

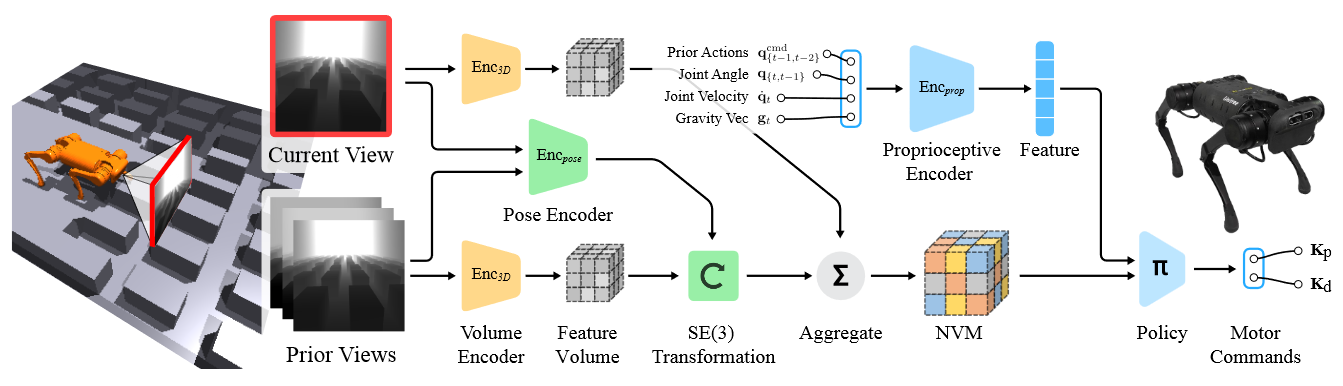

The following figure illustrates the architecture of the NVM method. As the first step, an encoder network $N_e$ receives a sequence of consecutive observations $O_t\cdots O_{t-n+1}$ and extracts feature volumes $V_t\cdots V_{t-n+1}$. The encoder network is a convolution-based network attached to a 3D convolution layer. It first extracts the image features as $(C, H, W)$ and then reshapes it to $(C/D, D, H, W)$ as a volume tensor. Then, the tensor is passed to a 3D convolution layer to apply further refining.

A second pose encoder network $N_t$ estimates the transformation $T_{t-1}^t\cdots T_{t-n+1}^t \in SE(3)$ between the current and the past observation. The pose encoder is a convolution-based network with two depth images stacked on a depth channel as input. After that, by aggregating estimated transformations to the feature volumes $V_{t-1}\cdots V_{t-n+1}$, we can get the NVM $V^M_t$ for decision-making. The aggregation function $f$ is usually a simple summation.

Formally, this process can be written as:

\[\begin{align*} V_i &= N_e(O_i) \\ T_i^j &= N_t(O_i, O_j)\\ V^M_t &= \frac{1}{n}(\sum_{i=t-n+1}^{t-1}f(V_i, T_i^t) + V_t) \end{align*}\], where $f$ denotes the function which apply transformation $T_i^j$ to feature volume $V_i$. This paper adds two additional 3D conv layers to refine the transformed feature volume instead of performing transformation directly in latent space.

During robot locomotion training, besides the reward function mentioned in the previous section, they also add a decoder network $N_d$ and a reconstruction loss as a self-supervised loss, which is defined as:

\[\mathcal{L}_{rec} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=t-n+1}^{t}|O_i, \hat{O}_i|\], where $\mathcal L_{rec}$ denotes the L1 loss and $\hat O_i = N_d(V_{t-n+1}, T_{t-n+1}^i)$ is the reconstructed observation from the decoder network $N_d$. Then, the overall training loss is given by:

\[\mathcal{L} = \lambda_{rec}\mathcal{L}_{rec} + \lambda_{BC}\mathcal{L}_{BC}\]And in their experiment, they use $\lambda_{BC} = 1$ and $\lambda_{rec} = 0.01$.

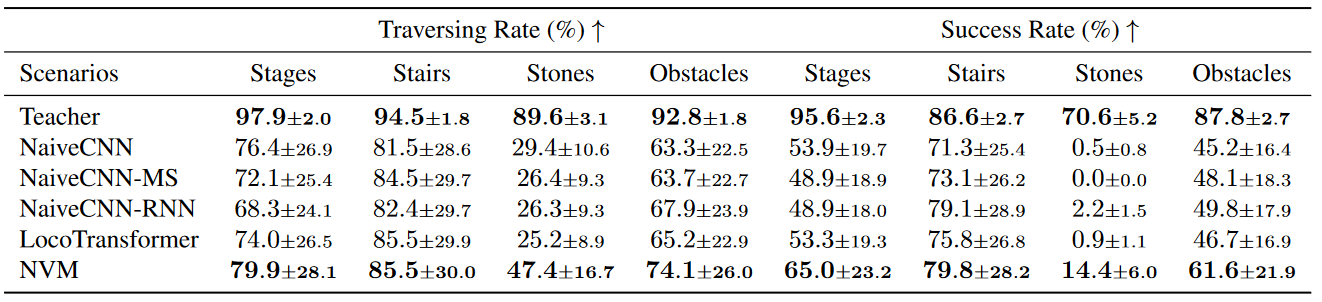

The simulation results comparison between NVM and other methods is shown in the following figure. NaiveCNN series are the structures we mentioned before, and the loco-transformer method utilizes a shared transformer model to perform cross-modal reasoning between visual tokens from 2D visual feature map and proprioceptive features. All the strategies are trained with imitation learning from teacher policy, which can be treated as an upper bound for all methods. The traversing rate is defined by the distance the robot moves dividing the reachable distance (the distance between the end of the environment and starting position), and the success rate is defined by the ratio of the robot reaching the end of the environment.

From the comparison, we may find that the NVM method outperforms other methods in both the traversing and success rates. Notice that NaiveCNN-MS introduces the mechanism of processing each frame of visual observation separately, and NaiveCNN-RNN uses a memory mechanism to process the observation sequence. However, both of them are inferior to the NVM method, which may indicate that the improvement brought by NVM is actually from explicitly modeling the 3D transformation instead of introducing more computation.

Motions beyond walking

Previous sections show the two-stage training framework accomplishes highly robust perceptive walking. After that, researchers consider more dynamic situations to enable the quadruped robots to perform agile maneuvers akin to their biological counterparts. The robot can learn to perform more naturalistic and dexterous actions using more self-craft sophisticated environments. In this section, we would like to introduce some research that lets the quadruped perform more motions beyond walking.

Parkour and extremely parkour

Parkour is a popular athletic sport that involves humans traversing obstacles in a highly dynamic manner, like running on walls and ramps, long coordinated jumps, and high jumps across obstacles. Boston Dynamics Atlas robots have demonstrated stunning parkour skills using model predictive control (MPC). However, massive engineering efforts are needed for modeling the robot and its surrounding environments.

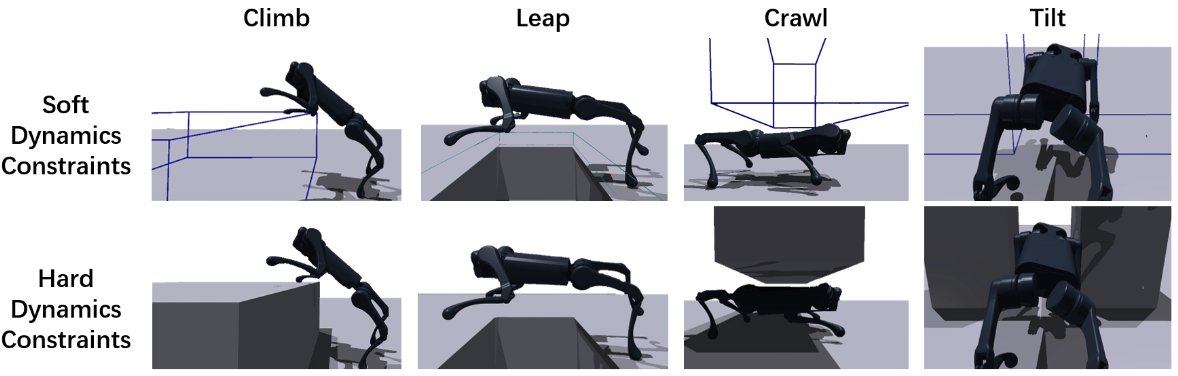

In [8], researchers follow the two-stage training process in Section 3 to train an end-to-end vision-based parkour skill, including climbing over high obstacles, leaping over large gaps, crawling beneath low barriers, squeezing through thin slits, and running. The privileged visual information includes the distance from the robot’s current position to the obstacle in front of the robot, the height of the obstacle, the width of the obstacle, and a 4-dimensional one-hot category representing the four types of skills, which is illustrated in the following figure. The four kinds of specialized skill policies $\pi_{{\text{climb, leap, crawl, tilt}}}$, which are formulated as GRU, are trained on corresponding terrains.

One thing noticed is that they use soft dynamics constraints during oracle policy training to solve the exploration problem due to the challenging obstacles. As shown in figure above, the obstacles are set to be penetrable so the robot can violate the physical dynamics in the simulation by directly going through the obstacles without getting stuck near the obstacles as a result of local minima of RL training with the realistic dynamics. To measure the degree of dynamics constraints’ violation, they sample collision points within the collision bodies of the robot in order to measure the volume and the depth of penetration as an additional reward $r_\text{penetrate}$. After pre-training with soft dynamics constraints, they fine-tune the policies with hard dynamics constraints.

During visual policy distillation, researchers use a single vision-based policy to perform all four skills, although oracle policies are trained separately. They use a CNN-based policy $\pi_\text{parkour}$ and random sampled tracks composed by obstacles listed above as distillation environments. The distillation objective is defined as:

\[\begin{align*} \arg\min_{\theta_\text{parkour}} &\mathbb{E}_{\textbf{O}_t, \hat{\textbf{O}}_t \sim \pi_\text{parkour}} [D(\pi_{i}(\hat{\textbf{O}}_t), \pi_\text{parkour}(\textbf{O}_t))] \quad i\in{\text{\{climb, leap, crawl, tilt\}}} \end{align*}\], which follows the definition in Section 3.

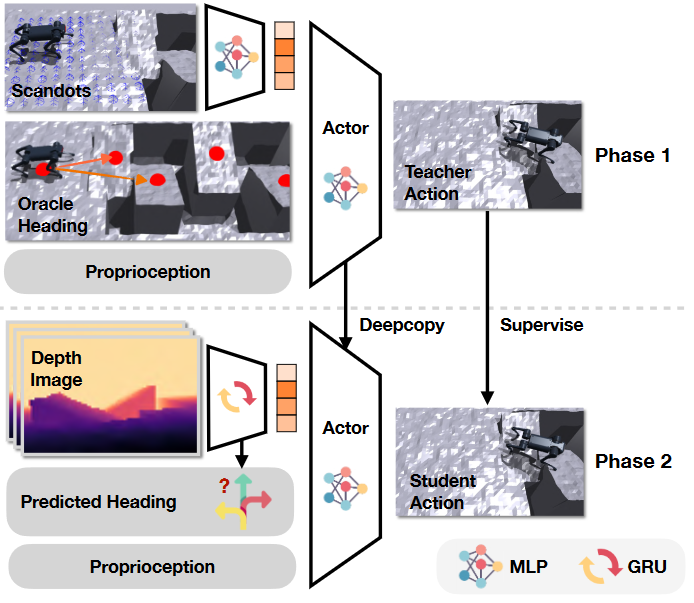

In another work concurrently, researchers propose oracle heading to assist direction with inquiry during oracle policy training in another parkour task [6]. The red dots in training framework phase 1 denote the waypoints used to compute directions $\hat{\textbf{d}}_w$ on the terrain as:

\[\hat{\textbf{d}}_w = \frac{\textbf{p}_{i} - \textbf{x}}{||\textbf{p}_{i} - \textbf{x}||}\], where $\textbf{p}_i$ is the next way point and $\textbf{x}$ is the robot’s current position. Then, the tracking reward during oracle policy training is defined as:

\[r_{\text{tracking}} = \min(\langle \hat{\textbf{d}}_w, \textbf{v} \rangle, v_{cmd})\]where $\textbf{v} \in \mathbb{R}^2$ is the robot’s current velocity in world frame and $v_{cmd} \in \mathbb{R}$ is the desired speed. Furthermore, in order to avoid the robot stepping close to the edge riskily, they add a penalty term $r_{\text{edge}}$ to the reward function as:

\[r_{\text{edge}} = -\sum_{i=0}^4 c_i\cdot M[p_i]\], where $c_i$ is $1$ if ith foot touches the ground. $M$ is a boolean function which is 1 if the point $p_i$ lies within 5cm of an edge. $p_i$ is the foot position for each leg.

Distilling the direction and exteroception of [6] also follows the process in Section 3 using RMA architecture and DAgger algorithm, and the framework is illustrated in the following figure. However, since directly using the predicted heading direction may cause catastrophic failure, they use a mixture of teacher and student. The heading direction sent to the student policy $\theta$ is defined as:

\[\begin{align*} \theta = \begin{cases} \theta_\text{pred} &\quad \text{if}\ |\theta_\text{pred} - \hat{\theta}_{\textbf{d}}| < 0.6\\ \hat{\theta}_{\textbf{d}} &\quad \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align*}\], where the $\theta_\text{pred}$ and $\hat{\theta}_{\textbf{d}}$ are the predicted heading direction and the oracle heading direction, respectively.

The real-world experimental results of these two papers show distinguished improvement of quadruped robot locomotion tasks. In [8], parkour policy can enable the robot to climb obstacles as high as 0.40m (1.53x robot height) with an 80% success rate, to leap over gaps as large as 0.60m (1.5x robot length) with an 80% success rate, to crawl beneath barriers as low as of 0.2m (0.76x robot height) with a 90% success rate, and to squeeze through thin slits of 0.28m by tilting (less than the robot width). And in [6], the robot can perform long jumping across gaps $2\times$ of its own length, high jumping over obstacles $2\times$ its own height, and running over tilted ramps, which are shown in the first figure.

From locomotion to manipulation

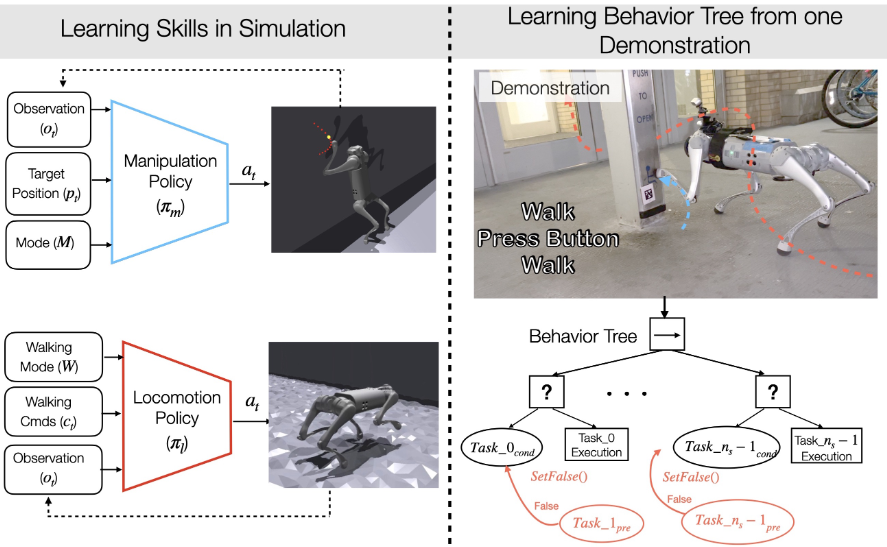

After training the robot to walk or run across challenging terrains, researchers try to train it to perform manipulation tasks using its legs like their biological counterparts [10]. This figure shows a method framework to let the robot press a button while keeping balance.

In this research, they decouple the problem into locomotion policy $\pi_l$ to walk and a policy to manipulate with legs $\pi_m$ because walking and manipulation using legs include drastically different joint angle behaviors. Again, these two policies are also trained using the two-stage training framework in Section 3. However, the manipulation policy’s goal is to follow a desired end-effector position $p^{cmd}_{foot}(t) = [p_x(t), p_y(t), p_z(t)]^T$ such that the foot can track any arbitrary pre-planned trajectory. Therefore, they added a position-tracking reward during oracle manipulation policy training.

In real-world deployments, they combine the above-learned skills from only one demonstration. Note this single long-range demonstration is only in the high-level action space where the human chooses what skill to follow and when the low-level control is taken care of by the skills $\pi_m, \pi_l$ learned above. They distill this single demonstration into a behavior tree to learn to complete the task robustly.

For agile navigation

Several methods have shown their abilities to enable the quadruped robot to act agilely, like parkour or manipulation. However, these methods are usually trained in a single environment, which is unsuitable for real-world deployment. For example, locomotion policy and manipulation policy are trained separately in [10], and the robot needs to switch between these two policies to perform different tasks. In this section, we would like to introduce some research that utilizes existing locomotion techniques for upstream tasks: agile navigation.

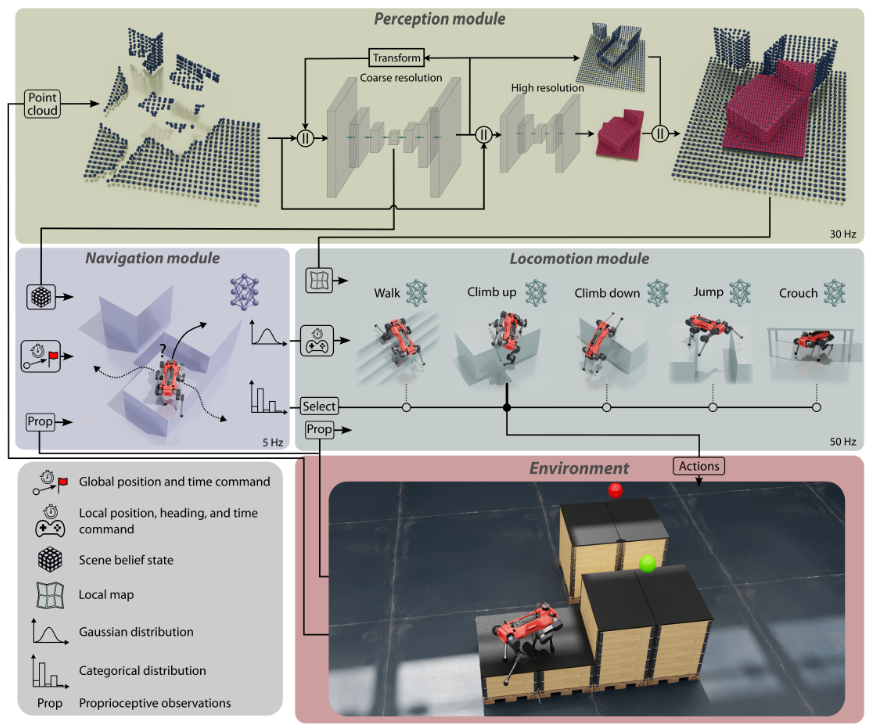

In [12], researchers use a hierarchical architecture with three components: a perception module, a locomotion module, and a navigation module, which are illustrated in the following figure. The locomotion module contains a catalog of locomotion skills that can overcome specific terrains. For this work, they train five policies that can walk on irregular terrain, jump over gaps, climb up and down high obstacles, and crouch in narrow passages. Using the latent tensor of the perception module, the navigation module guides the locomotion module in the environment by selecting which skill to activate and providing intermediate commands. Each of these learning-based modules is trained in simulation.

Although the output of the locomotion module is the same as previous introduction, it takes the inputs from the navigation module, including index of selecting navigation skills $s$ and target base heading $\phi$. Comparing with the previous parkour papers [8][10], the arrangements of terrains and obstacles are randomly, thus the robot needs to follow the commands provided by navigation module to turn its directions and adapt different commands instead of following a fixed trajectory or just going forward.

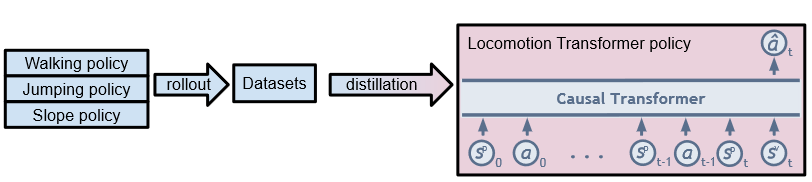

Another solution to this issue is distilling all the skills into a single policy, thereby removing the necessity for ad-hoc switching between individual specialist policies and promoting generalization capabilities to different obstacle and terrain configurations. In [13], researchers propose a transformer-based generalist locomotion policy to finish a self-designed obstacle course benchmark, which is illustrated in the following figure.

They first train three individual specialist policies and then collect an offline dataset by rolling out them in simulation environment environments like random gaps, stairs and slopes. Then they use a casual transformer based generalist policy to take velocity command, proprioceptive states, and recent visual observation over a fixed context window as input and output the target joint angles in next time steps.

Conclusion

Sim-to-real methods using deep reinforcement learning in quadruped robot locomotion represent a significant advancement in robotics. It allows these robots to navigate complex environments more effectively and autonomously, adapting to new challenges in real time. This topic has been studied extensively in recent years, and we have seen many impressive developments to let the robot finish locomotion on different kinds of intricate terrains.

However, certain instances can occur where the robot fails because of a visual or terrain mismatch between the simulation and the real world. The only solution to this problem under the current paradigm is to engineer the situation back into simulation and retrain, which poses a fundamental limitation to this approach. Furthermore, real-world physical properties are difficult to model accurately in simulation. Frictions and rigidity are significant for quadruped robots to perform actions like jumping and climbing. These properties are difficult to model accurately in simulation.

References

Lee J, Hwangbo J, Wellhausen L, Koltun V, Hutter M: Learning quadrupedal locomotion over challenging terrain. Science robotics 2020, 5:eabc5986.

Kumar A, Fu Z, Pathak D, Malik J: Rma: Rapid motor adaptation for legged robots. arXiv preprint arXiv:210704034 2021,

Agarwal A, Kumar A, Malik J, Pathak D: Legged locomotion in challenging terrains using egocentric vision. In Conference on Robot Learning. . PMLR; 2023:403–415.

Smith L, Kew JC, Li T, Luu L, Peng XB, Ha S, Tan J, Levine S: Learning and adapting agile locomotion skills by transferring experience. arXiv preprint arXiv:230409834 2023,

Feng G, Zhang H, Li Z, Peng XB, Basireddy B, Yue L, Song Z, Yang L, Liu Y, Sreenath K, et al.: Genloco: Generalized locomotion controllers for quadrupedal robots. In Conference on Robot Learning. . PMLR; 2023:1893–1903.

Cheng X, Shi K, Agarwal A, Pathak D: Extreme parkour with legged robots. arXiv preprint arXiv:230914341 2023,

Rudin N, Hoeller D, Reist P, Hutter M: Learning to walk in minutes using massively parallel deep reinforcement learning. In Conference on Robot Learning. . PMLR; 2022:91–100.

Zhuang Z, Fu Z, Wang J, Atkeson C, Schwertfeger S, Finn C, Zhao H: Robot parkour learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:230905665 2023,

Fu Z, Cheng X, Pathak D: Deep whole-body control: learning a unified policy for manipulation and locomotion. In Conference on Robot Learning. . PMLR; 2023:138–149.

Cheng X, Kumar A, Pathak D: Legs as Manipulator: Pushing Quadrupedal Agility Beyond Locomotion. arXiv preprint arXiv:230311330 2023,

Jeon S, Jung M, Choi S, Kim B, Hwangbo J: Learning Whole-body Manipulation for Quadrupedal Robot. arXiv preprint arXiv:230816820 2023,

Hoeller D, Rudin N, Sako D, Hutter M: ANYmal Parkour: Learning Agile Navigation for Quadrupedal Robots. arXiv preprint arXiv:230614874 2023,

Caluwaerts K, Iscen A, Kew JC, Yu W, Zhang T, Freeman D, Lee K-H, Lee L, Saliceti S, Zhuang V, et al.: Barkour: Benchmarking animal-level agility with quadruped robots. arXiv preprint arXiv:230514654 2023,

Bojarski M, Del Testa D, Dworakowski D, Firner B, Flepp B, Goyal P, Jackel LD, Monfort M, Muller U, Zhang J, et al.: End to end learning for self-driving cars. arXiv preprint arXiv:160407316 2016,

Ross S, Gordon G, Bagnell D: A reduction of imitation learning and structured prediction to no-regret online learning. In Proceedings of the fourteenth international conference on artificial intelligence and statistics. . JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings; 2011:627–635.

Miki T, Lee J, Hwangbo J, Wellhausen L, Koltun V, Hutter M: Learning robust perceptive locomotion for quadrupedal robots in the wild. Science Robotics 2022, 7:eabk2822.

Yang R, Yang G, Wang X: Neural volumetric memory for visual locomotion control. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. . 2023:1430–1440.

Kareer S, Yokoyama N, Batra D, Ha S, Truong J: Vinl: Visual navigation and locomotion over obstacles. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). . IEEE; 2023:2018–2024.

Pinto L, Andrychowicz M, Welinder P, Zaremba W, Abbeel P: Asymmetric actor critic for image-based robot learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:171006542 2017,

Nahrendra IMA, Yu B, Myung H: Dreamwaq: Learning robust quadrupedal locomotion with implicit terrain imagination via deep reinforcement learning. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). . IEEE; 2023:5078–5084.

Schulman J, Wolski F, Dhariwal P, Radford A, Klimov O: Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:170706347 2017,

Peng XB, Ma Z, Abbeel P, Levine S, Kanazawa A: Amp: Adversarial motion priors for stylized physics-based character control. ACM Transactions on Graphics (ToG) 2021, 40:1–20.

Lai Z, Liu S, Efros AA, Wang X: Video autoencoder: self-supervised disentanglement of static 3d structure and motion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. . 2021:9730–9740.